|

|

Brossac

Village

|

|

Brossac village has all one needs to compliment

a

stay in The Southwest of France

Brossac

History

|

The

Charente During WWII

Following the German invasion of

France in May of 1940 and the

subsequent split of the nation into so-called ‘free’ and ‘occupied’

zones, the region of Charente was cut in two by the demarcation line,

which ran straight through Vienne, Charente, Dordogne, Gironde, and the

Basses-Pyrénées. Of the five administrative regions of occupied France,

Brossac and the rest of the occupied Charente fell into Région B, which

had its German headquarters at Angers.

In

1942, in retaliation for the Allied campaign Operation Torch in North

Africa, French and Italian forces invaded and occupied the so-called

‘free zones,’ reuniting all of France - and the two zones of the

Charente - under a Nazi dictatorship until liberation by Allied forces

in 1944.

|

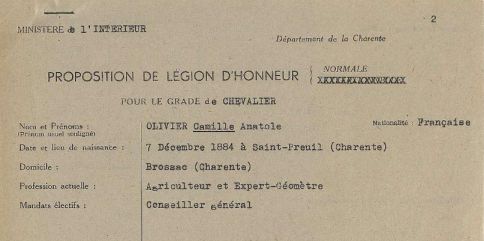

Person

of Interest: Camille Olivier

Camille Anatole Olivier (born 7 Dec.

1884) was the mayor of the canton of Brossac from 1935-1940, and also

held the position of Conseiller Général of the Charente from 1934-1940

and again from 1945-1964. His first term for both positions was

interrupted by a Nazi crackdown in the German Charente from 1940 until

the end of the war, during which the positions of mayor and

Conseiller Général were eliminated following a series of

push-backs from the French Resistance in the region. Though Brossac had

been under German control since June, local management had been allowed

to remain, and it was not until after the August rebellions that the

German High Command became the sole administrator of the region.

Olivier,

however, was no stranger to war - he had served in the First World War

from 1915 to 1918, and retained close ties to the French military and

government throughout the remainder of his life. Before commencing his

political career in 1925 (at which point he became the Conseiller

d'Arrondissement of Charente), Olivier studied Agriculture and Geometry

and became an agriculturalist on his farm in Brossac. In 1950, he was

was made a Chevalier in the Légion d’Honneur for his work for the

people of the Charente (and of Brossac in particular - it is referred

to as his ‘petite partie charentaise’ in the official report), and in

1958 he made the rank of Officier. (Click here to

read more about the Légion d’Honneur).

After

the war, Olivier resumed his position as Conseiller Général of

Charente, and by all accounts continued to serve the people of Brossac

and all of the Charente wholeheartedly.

Click

here for Olivier's official documents

|

Group

of Interest: La Résistance in Chalais

The

main resistance movement in the Charente during the war were the Maquis

- rural bands of guerilla fighters that served as a liaison between

different resistance groups such as the Resistance Fer (railway

employees) and the Resistance de Sapeurs Pompiers (firefighters) in the

South of France. While Claude Bonnier was in charge of training

resistance fighters in the whole of South-West of France, Jacques

Nantes was the man delegated to train saboteurs in the

Charente, Charente-Maritime, and Bordeaux. The Maquis in Chalais were

especially famed for one insurgency in particular which played out in

early September of 1940, about two months after German occupation.

The

Chalais Maquis' claim to fame centered around their prolific cutting

of German telephone lines in the region, much to the annoyance of the

Germans. Following an especially damaging stint on the 26th of

August, Colonel Kretschmann of the Nazi Army issued a

statement

promising to ‘encore une fois prendre des sanctions contre les communes

et leur population’ - implement further sanctions on the population of

Charente (which, as it turned out, included the elimination of the

positions of mayor and Conseiller Général, putting Camille Olivier out

of a job). Any further vandalizing of German communications,

Kretschmann decreed, was outlawed ‘sous peine de mort’ (under

pain of death).

On

August 28th, Alfred Ferrand, a Maquisard of Chalais, was beaten

by

German police for his participation in the August 26th operation and

was found by his comrades on the road between Rue La Petitie and Rue

Bouex. Ferrand, sadly, died in hospital from his wounds,

inciting intense anger in Maquis circles. Then, five days later,

another Maquis member by the name of Jean Ratouit was found beaten and

left out in his fields at Chez Grosiac to die. Resentment in the

Chalais Maquis reached its height. In early September, a new wave

of cutting of communications took place, spurred by a desire to avenge

the death of Ferrand and the beating of Ratouit.

The

Germans, of course, were furious - with the help of the French police,

an investigation was immediately launched into the operations of the

Chalais Maquis, which proved surprisingly fruitless. Did the French

police willingly turn a blind eye to the operations of Maquis, as a way

of quietly rebelling against their German overlords? Or were the

Chalais Maquis just particularly skilled in covering their tracks?

Though we’ll never know for sure, the legend of the Maquis Chalais

serves as a great testament to the people of this small region, and is

one of the many inspiring stories of civilian resistance in the Second

World War.

|

Event

of Interest: Jewish Raids in the Charente and Limousin

Following

the formulation and fine-tuning of the Nazi’s ‘Final Solution to the

Jewish Question’ at the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, a number of

Jewish raids took place in the Charente and the neighboring region of

Limousin, which is about 30 minutes away from Brossac by car. According

to the AJPN (L’Organisation pour les Anonymes, Justes et Persécutés

durant la période Nazie dans les communes de France), these raids were

carried out by local German police forces under the command of the

Regional Prefects (Préfets Régionaux) of the Charente and Limousin

regions. From a police report sent by the General Secretary of Limoges

police force (a town about two hours from Brossac), we discover that

certain categories of Jewish people were in fact exempt from these raid

orders - specifically, pregnant women, people over 60, and

unaccompanied minors.

The

Limousin raid took place on 26th of August 1942 and resulted in

the

capture and deportation of 446 Jews, 68 of whom were children. The

captives were transported to a camp in Nexon, a town about half an hour

south of Limoges, where they were then boarded onto transport headed

for the town of Drancy (near Paris) three days later. From there,

according to AJPN records, the detainees were then boarded onto

convoyes labelled numbers 26 and 27, heading straight for Auschwitz.

A

little over a month later, on the nights of October 8th and 9th,

two more Jewish raids took place in the Charente. While the AJPN

unfortunately has no records for the number of people deported in these

raids, we can be sure that it devastated the lives of numerous

Charentais, leaving deep scars in the region for years to come.

|

This article was researched and written by Aina Swartz a volunteer at La Giraudiere who was from the USA

References for this article.

Websites:

http://memorial16.free.fr/anglais/occupation.htm#res1

http://www.ajpn.org/commune-Brossac-16066.html

http://www.map-france.com/Brossac-16480/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_military_administration_in_occupied_France_during_World_War_II#Occupation_zones

http://www.parolesderesistants.com/

Books:

Jacques Baudet et Hugues Marquis, La Charente en Guerre (1939-1945)

H. R. Kedward, In

Search of the Maquis: Rural Resistance in Southern France |

This

website was produced by volunteers and interns from La

Giraudiere. To read more about their contribution and how this

subdomain was created, please visit Brossac Website

Creators you will also find a link to our Site Map

and our contact

information

|

|

|